Vayeshev 2022

Rabbi Philip Weintraub

Congregation B’nai Israel

December 17, 2022

At coffee this week, I spoke about the active verbs that name the parshas of the Jacob saga—Vayetze Vayishlach and Vayeshev. Jacob goes out, leaving his home, he sends messengers to his brother and finally, after that reconciliation he is able to truly settle down. As soon as he is settled in the land, the focus shifts, we look away from Jacob and look at the next generation—Joseph and his brothers. Many of us may be familiar with the narrative of the technicolor dreamcoat, Joseph being sold into slavery, Joseph’s rise and fall in Egypt, which ends this week with him in jail with the servants of Pharaoh, interpreting their dreams. We may be less familiar with the aside, the story of Judah and Tamar, found in chapter 38 of this week’s parsha.

Before reminding you of the story, Tamar is ancestor of King David. Her revolutionary choices lead to her being seen as a worthy ancestor of our once and future king. Tamar takes her destiny into her own hands, fulfilling the word of God, even if in ways we might have difficulty with today. Judah has three sons, Er, Onan and Shelah. Er marries Tamar, but he is displeasing to God, who smites him. Following the tradition of Levirite marriage, Onan marries Tamar, in order to provide offspring that have Er’s name on them. (Side note to the side note, Onan’s sin is not what is now called Onanism, but coitus interruptus!). Onan is then struck down by God for refusing to father a child. After seeing two sons struck down by God, Judah thinks that maybe Tamar is the problem, and hides away Shelah from her, sending her back to her father’s house—leaving her in an undetermined state—she is effectively married to Judah’s family—she cannot remarry—but neither is she truly connected. After some time, Tamar decides the situation is untenable and takes things into her own hands. She dresses as a cultic prostitute and plants herself in Judah’s path to market. He impregnates her and leaves his staff and cord (his ID) with her until he can return with payment. When he sends his servant later to pay her, he finds she has disappeared and no one remembers seeing her! Shortly thereafter, Tamar is noticeably pregnant, causing shame upon Judah, since it shows that 1) the family has not fulfilled its obligations and 2) Tamar has effectively committed adultery. He moves to have her killed for that crime. Rather than shouting from the rooftops that Judah is the father, she sends a message to Judah “It’s by the man to whom these belong that I’m pregnant—examine these-whose seal and cord and staff are these?” Judah recognizes them and says “She is more right than I, inasmuch as I did not giver her to my son Shelah.” They don’t continue their relationship, but the twins Pererz and Zerach are born to her.

A number of years ago, I attended a seminar at Yeshiva Hadar in New York. While traditionally, we may know that in many cases if someone threatens us with death, we can violate many prohibitions. There are three that we do not violate under any circumstances—idolatry, sexual immorality and murder. At least that is what most people imagine. There is actually one more—publicly humiliating someone. It is a variation on the murder theme—but perhaps even worse—since with murder you die only once whereas public humiliation can result in feeling like you are dying again and again and again!

The story of Tamar is the prooftext for this 4th inviolable sin. Tamar could have publicly embarrassed Judah, but instead, she used incredible discretion. If someone put me on death row, I might imagine I would use every tool at my disposal to free myself! She found a way to acquit herself far more discreetly!

We often think that women are secondary in the Torah. We hear the stories of the patriarchs, the kings and the prophets; yet the most vital lessons of our tradition are often taught by women! Sarah, Hagar, Rebecca, Rachel, Leah, Tamar, Miriam, Zipporah, the daughters of Tzelophad, Hannah, Devorah and so many others, are not silent accomplices, but protagonists in their own rights. They are essential to the narrative. They do not merely listen to God, but demand of God. They speak up for their rights and the rights of others. They act and change history. They also show that to lift up one’s voice is not ALWAYS to be the center of attention, but can be done more quietly, too—as Tamar does today.

The lesson of Tamar, to do what needs to be done AND not shame others is a lesson that seems lost in today’s world. We see again and again that political debate becomes more and more shameless. We see people make baseless accusations in person and online with the sole purpose of insulting and degrading others. The Torah, Jewish tradition does not stand for that. It demands a higher standard. It requires consideration in our speech and in our actions. Tamar would have a lot to say about our world today!

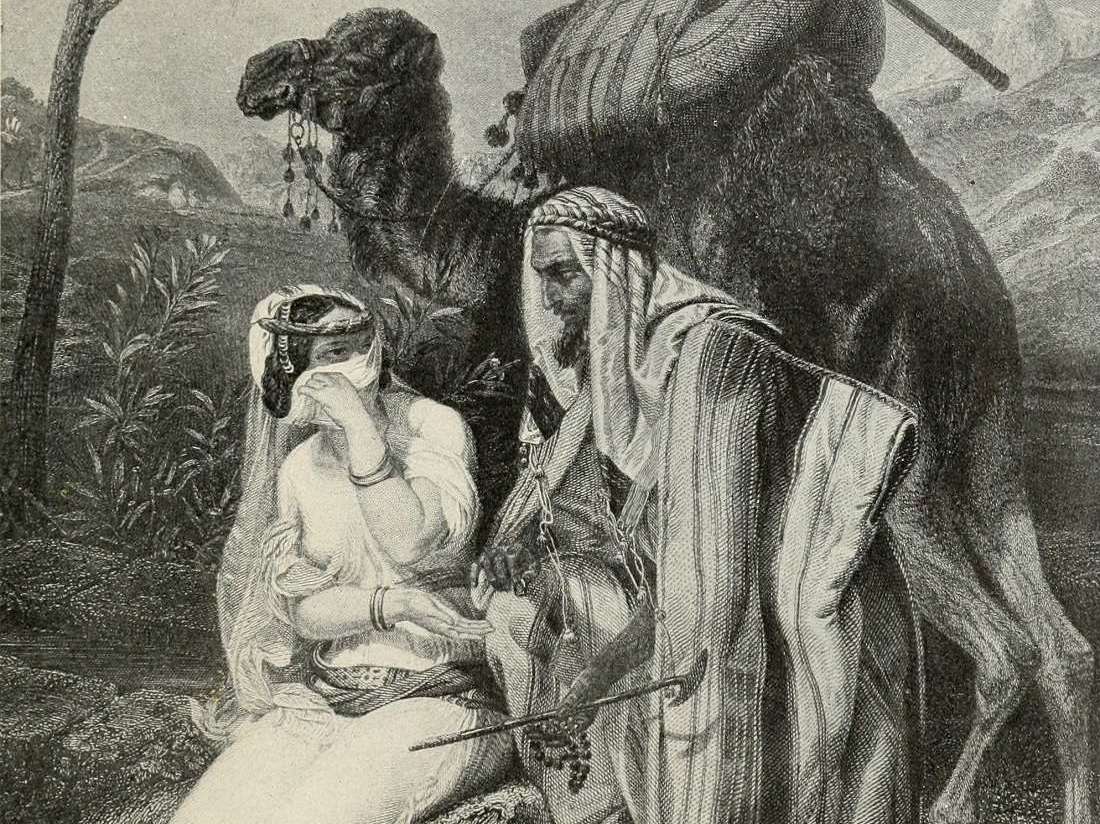

Judah and Tamar. Horace Vernet (1789–1863)

Comments

Post a Comment